May wine –

done right!

Quantitative HPLC analysis of coumarin in alcoholic woodruff extracts

Dr. Brigitte Bollig, Shimadzu Europa GmbH

When scouring the internet for recipes for May wine, you’re sure to come across very different, sometimes contradictory information on how long you should leave the woodruff to infuse in the wine. What you don’t want is to extract too much of the potentially toxic coumarin contained in the plant into the wine. But how long should you perform an extraction of woodruff leaves so that you don’t end up with a harmful amount of coumarin but still get the characteristic flavor of the finished May wine? This question was investigated using HPLC analysis and photodiode array detection.

Shimadzu LC Product Manager, Dr. Gesa Schad, recently recalled how the use of woodruff in May wine is a popular spring tradition in Germany. When she first started looking for May wine recipes, she was aware that woodruff contains the natural flavoring coumarin, which can be harmful to health in high doses. But when she was researching recipes, she realized: There are huge differences in the recommended “extraction time”, meaning how long the dried woodruff can be left in the wine without running the risk of reaching the permitted limits for coumarin. On one site, the maximum permissible “infusion time” was 45 minutes, while another stated that the plant should be left to infuse in the wine “for 1–3 hours, depending on the desired flavor intensity”.[1–4] So what should you do if you want to make a wine that has a nice woodruff flavor but without a dangerous coumarin content? Dr. Schad’s curiosity as a researcher was sparked! In order to be able to make a scientifically sound recommendation, it was first necessary to analyze the coumarin content in woodruff extracts with various extraction times. Her colleague at the time, Robert Ludwig, carried out the test series. The results of his quantitative determination are analyzed in more detail in this article in light of the established limits for coumarin in foodstuffs. The results are explained at the end, along with the recommendation on how to safely prepare May wine.

Table 1 gives an overview of the maximum levels of coumarin permitted by law in certain compound foods where flavorings and/or food ingredients with flavoring properties have been added (coumarin is permitted in these food ingredients and in flavorings, whereas coumarin as such may not be added to foods).[5]

|

Compound foods where the amount of coumarin is restricted |

Maximum amount of coumarin (in mg/kg food) |

|

Traditional and/or seasonal bakery products where cinnamon is indicated on the label |

50 |

Breakfast cereal products including muesli |

20 |

Fine bakery products other than traditional and/or seasonal bakery products where cinnamon is indicated on the label |

15 |

|

Desserts |

5 |

There is no defined limit value for beverages, however, the tolerable daily intake (TDI) value can be taken into account to assess the results described below [6], where a daily intake of 0.1 mg coumarin per kilogram of body weight is considered harmless.

Gesa Schad harvested woodruff from a commercially available plant and dried the parts of the plant overnight. Once dried, she tied together 3 g of the cut stems with a string and hung them upside down in 90 ml of white wine for extraction (a ratio of woodruff to wine commonly used for extraction in recipes), without immersing the cut ends in the liquid. Samples were taken at different times, which were filtered only through a 0.45-μm filter before injection into the HPLC (High Performance Liquid Chromatography). Robert Ludwig carried out the HPLC method on a Nexera XS system with binary pumps and a PDA detector.

The analytical conditions are listed in Table 2.[7]

|

System: |

Nexera XS |

|

Column: |

Shim-pack™ GIST-HP C18 (150 mm × 3.0 mm I.D., 3 μm) |

|

Flow rate: |

0.8 mL/min |

|

Mobile phases: |

A) Water |

|

Time schedule: |

50 % B (0.00–2.00 min) → 60 % B (4.00 min) |

|

Mixer: |

180 μL |

|

Column temperature: |

25 °C (77 °F) |

|

Injection volume: |

5 μL |

|

Detection (PDA): |

Coumarin: 280 nm (SPD-M40) |

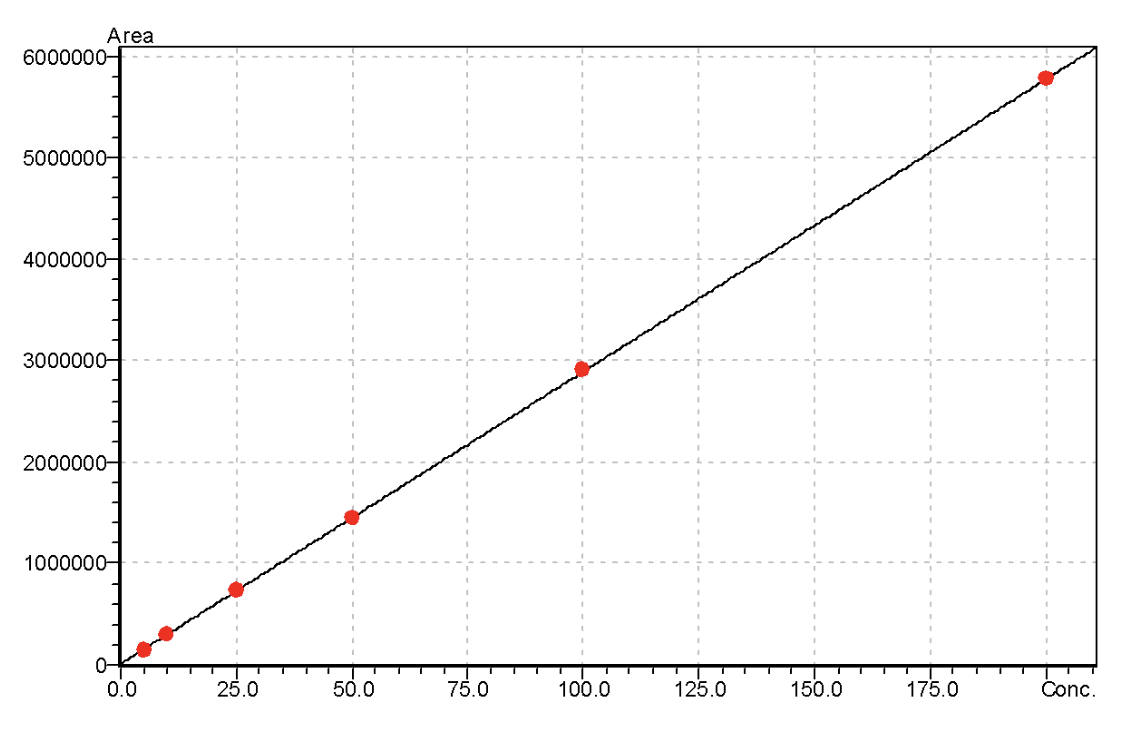

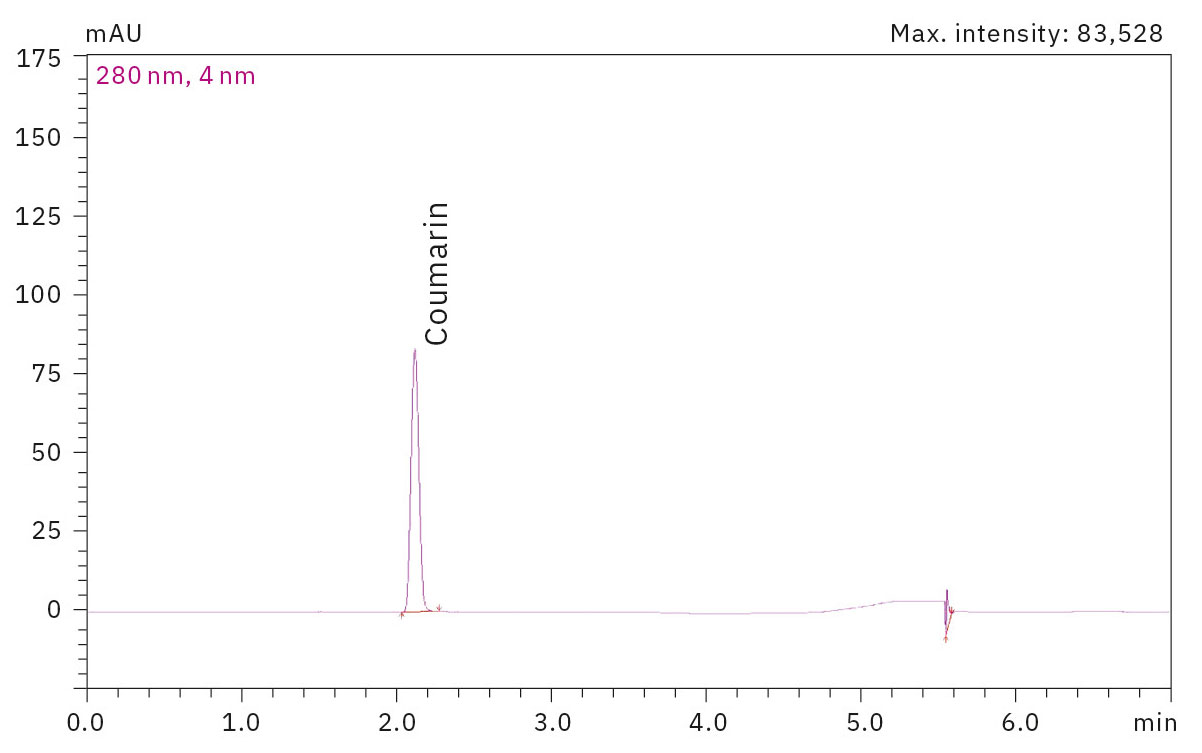

The standard concentrations used to create the calibration curve in Figure 1 are 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200 mg/L and result in a very good linearity of R2 > 0.99999.

The same analytical conditions were then used to analyze the extracts from woodruff leaves in white wine so that the coumarin content could be determined accordingly.

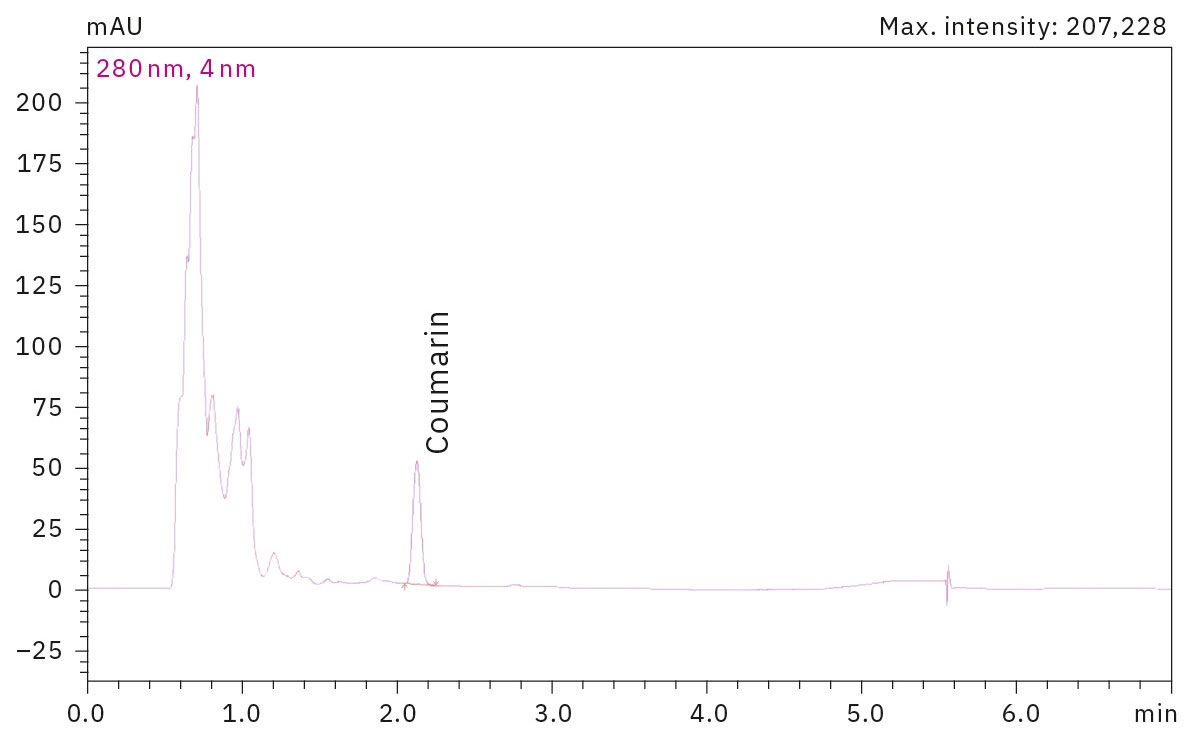

A chromatogram of the extract after 60 minutes in Figure 3 shows a very good separation of the coumarin from the earlier eluting matrices, which were extracted from the woodruff leaves as well as the coumarin and so cannot be seen in the standard measurements (Figure 2).

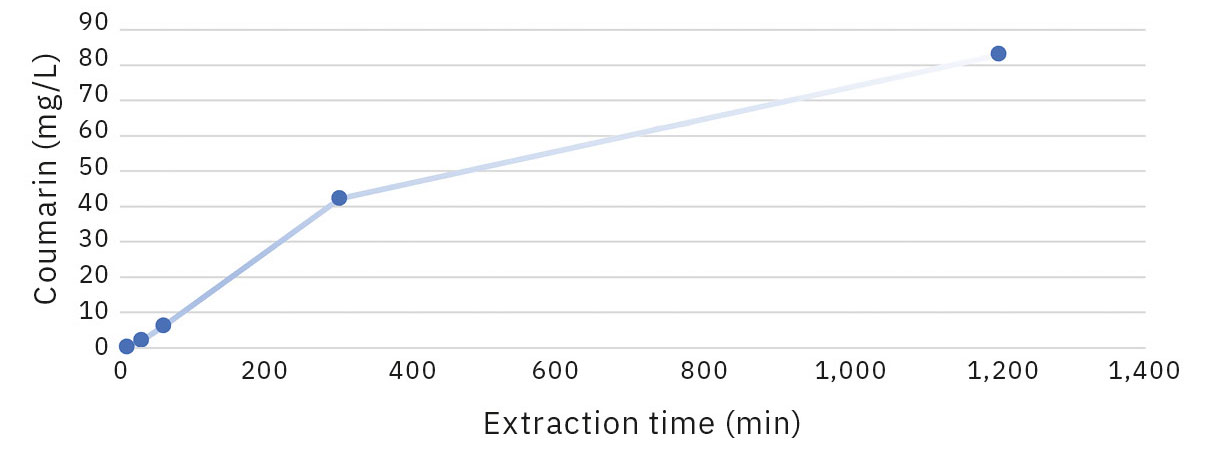

The two graphs in Figures 4 and 5 were created to illustrate the coumarin content determined as a result of the different extraction times of 10, 30 and 60 minutes as well as 5 and 20 hours (300 and 1,200 minutes). This clearly shows that the concentration of coumarin in the sample increases continuously over the entire duration of the experiment.

Extraction of coumarin from woodruff leaves

Table 3 shows these results of the determination of the coumarin content of 3 g woodruff in 90 mL white wine as a result of the extraction time (columns 2 and 3). For a whole bottle of wine, i.e. 750 mL, you would use about 25 g of dried woodruff (column 4 shows the coumarin content). This one bottle of white wine is then diluted with a second bottle of white wine and a bottle of sparkling wine to make the finished product (2.25 L). The last column shows the coumarin content in a glass of May wine (250 mL).

|

Extraction time (min) |

Coumarin (mg) in the sample (converted to 1 L) |

Coumarin (mg) in the sample (converted to 1 mL) |

Coumarin (mg) in 0.75 L white wine (also applies to 2.25 L of finished May wine) |

Coumarin (mg) in a 250-mL glass of the finished May wine |

|

10 |

0.238 |

0.000238 |

0.18 |

0.02 |

|

30 |

2.139 |

0.002139 |

1.60 |

0.18 |

|

60 |

6.163 |

0.006163 |

4.62 |

0.51 |

|

300 |

42.229 |

0.042229 |

31.67 |

3.52 |

|

1,200 |

82.966 |

0.082966 |

62.23 |

6.91 |

This means that thinking a harmful amount of coumarin could be contained in the May wine if the infusion time is too long is quite justified at first glance. However, if you take a closer look at the absolute values of the coumarin content in the finished May wine (column 5), you will notice that a quantity of 6.9 mg was only obtained in a glass of wine after 20 hours of extraction. Based on an average adult with a body weight of 60–80 kg, the limit value of pure coumarin that can still be consumed without any issue is 6–8 mg.

Fans of May wine can breathe a sigh of relief

HPLC was used as a very reliable analytical method to determine the final concentration of coumarin in alcoholic woodruff extracts. The results of the analysis show a significant increase in the coumarin concentration in the white wine used for the extraction over several hours. However, the concentration in a glass of wine only reaches harmful levels for an adult after at least 20 hours. If you keep the extraction time under 5 hours and don’t drink the 2 liters of wine alone, no harmful side effects of coumarin are to be expected. That means the taste and not the potentially toxic effect of woodruff should determine the length of exposure time. Please note: If the woodruff hangs in the wine for too long, the end product becomes bitter. Just try it for yourself!

[1] https://www.chefkoch.de/rezepte/668471168850775/Maibowle.html

[2] https://www.lecker.de/klassische-maibowle-73524.html

[3] https://www.essen-und-trinken.de/rezepte/maibowle-rezept-12509104.html

[4] https://eatsmarter.de/lexikon/warenkunde/kraeuter/waldmeister

[5] Official Journal of the European Union. REGULATION (EC) No. 1334/2008 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL dated December 16, 2008. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2008:354:0034:0050:de:PDF

[6] European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR). https://www.bfr.bund.de/de/fragen_und_antworten_zu_cumarin_in_zimt_und_anderen_lebensmitteln-8439.html

[7] Application News. 01-00233-EN. Iwata, N. https://www.shimadzu.com/an/sites/shimadzu.com.an/files/pim/pim_document_file/applications/application_note/14423/an_01-00233-en.pdf